Why I’m Starting A Million Things At Once — Only To Quit In Like 3 Months

Every new pursuit can build up the future of others.

My Name’s Jack

There’s this saying that it’s better to be good at one thing than mediocre at many things. Well, I never took that advice. I cannot for the love of me stick with doing one thing for long.

Okay, maybe that’s a little inaccurate to say. I can technically stick with working on something for a long time. I’ve done it before. But it’s often mixed with months of hitting walls and absolute misery.

I find myself constantly chasing the thrill of beginning anew again. As a result, I have about a billion different activities that I’ve partaken in. Some of which I continue to do... sort of.

But for others, I’ve largely given up on them.

During the pandemic, and now these mostly post-COVID years, I’ve purchased a VR headset. I’ve bought a 3D printer and made a ton of useless stuff with it. I brought out my 15-year-old piano and tried to learn a song.

Yet at the present moment, that headset goes weeks without usage. I’ve only printed a single object this year (a big sword that falls apart). And my piano’s been back in the closet for ages now.

Looking back at many of the now-depreciated activities I used to partake in, I’ve begun to notice this trend. It isn’t a hard and fast rule, but generally, it seems that three months is usually my wall of progression.

The Three-Month Cycle

This is how things typically go. In the first month of a new endeavor, I’m still learning the ropes. I don’t know what I’m doing half the time, but I know I’m making progress.

I try to figure out what exactly I want out of it all. What my goals are, how I’m going to achieve them, etcetera etcetera. I begin working my way through the first steps, and gradually gain a bit of confidence.

Usually by the second month, I’ve become acclimated to whatever the process is. Whether it’s the writing platform, the code base, or the ocean I’m fishing in.

This is when I can really start getting things done.

And so I spend more and more time working on it or playing around. It fuels my enjoyment, knowing what I can do with it. And that sparks motivation for me to do it even more.

I keep doing and doing it, exploring all the different ideas and possibilities I could do with the activity. But eventually, that inspiration I’m drawing from starts to dwindle. The ideas then revert back to a more normal level.

That brings me to month 3. I continue to try and squeeze more enjoyment and ideas out of it. But it becomes harder with each day. The rose-tinted glasses start coming off, and the less glamorous side starts to show.

Things just don’t feel as fun anymore…

By the beginning of the fourth month, I’m usually exhausted with everything. It becomes a chore to even continue. As one might guess, this can give me enough reason to quit entirely.

The honeymoon is over.

Again, it isn’t a hard and fast rule. Sometimes it takes longer, sometimes it takes less time. But generally, I usually have a point of considerable growth, followed by an equally considerable slowdown.

This very writing endeavor on Medium is an example of that. In the first month, I was still getting used to the platform and writing again. Formatting and structure were a bit difficult for me to get right.

In the second month, I had eventually become acclimated. I had loads of ideas I wanted to write about, I found a style, and it was awesome to see connections being made through reading and writing.

That April, I published an article almost every single day.

But then May came, and that fervor was starting to fade. I was running out of anecdotes that I could easily put into writing. And the less enjoyable aspects of Medium were becoming more apparent.

That month, I was back to publishing two articles a week. But near the end, I couldn’t even do that. Things were really starting to taper off.

As of the time of writing, it’s now the fourth month. And it’s really a struggle to write anything at all. I have a few ideas, but not much direction nor motivation to structure what I want to write.

Overall, I really care a lot less, and the emotional high has faded into this monotony. It just feels a lot more like busy, routine work. Which I guess, it sort of is now. Nothing I put out there makes me feel that good anymore.

“Whatever… good enough. Just publish this mess already.”

This is the pattern I’ve observed throughout many of my hobbies and areas of work.

Don’t get me wrong, I haven’t given up entirely. But as mentioned, it’s much rarer that I get on and write. There have been many other activities that I’ve largely ceased as well.

Yet I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing.

Zooming Out

First of all, one does have to question what it truly means to give up. When I hear that phrase, I assume it’s over. I’m never going to touch on that pursuit again, and everything I had done was for nought.

However, I don’t believe that’s true. There’s nothing stopping me from picking it back up again in a month. Or in another year. Hell, even in another 10 years.

If and when I do, one could consider that more of a continuation rather than a new beginning. Sure, it’s entirely possible that much of my knowledge and memories will have diminished by then.

But to the contrary, I don’t believe that experience goes away completely.

Being 22 at the time of writing, I haven’t had a lot of opportunities to give up on things for ten years. But sometimes, for example, a topic I learned about years ago will come back to light.

There’s a sense of familiarity and remembrance. Soon, the knowledge starts rushing back. Getting caught back up to the speed I was at takes a lot less time than it did at first.

Additionally, I’ve had experiences in other areas since I ceased engaging with the activity the previous time. And oftentimes, they help me progress even further than I was capable of before.

New angles, new information, etc.

They unlocked new frontiers to be explored.

It’s kind of like a prestige function in an idle clicker game. I buy all my upgrades and automation, and eventually reach a point where progression stalls.

So I start “anew” after a reset period. But with the prestige upgrade, I reach that same point from before much faster, and eventually surpass that point to reach even higher scores.

It’s not exactly a one-to-one comparison, but I see it as something akin to that. These past experiences are establishing baselines to ramp off of in the future, so starting again takes less time and effort.

And what’s great is, they don’t even have to be closely related.

Ramp Up, Taper Down

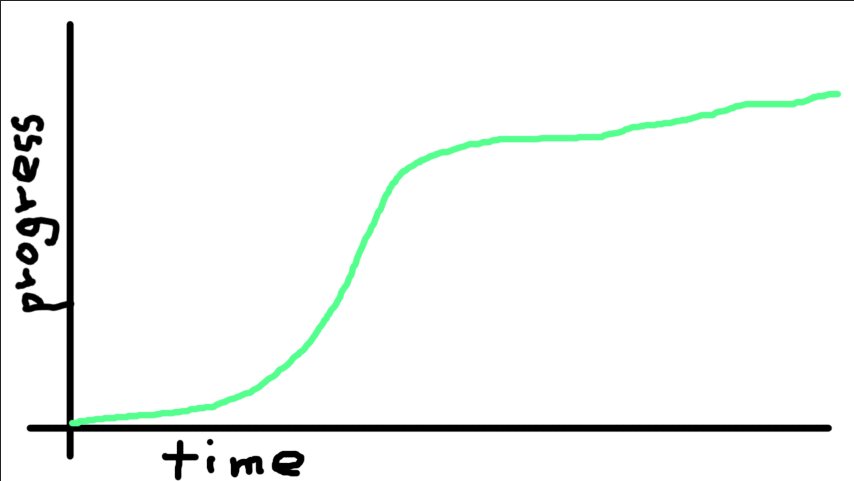

It is said that scientific progress generally follows what’s called a Sigmoid curve, where things remain slow or stagnant for awhile, before an explosion of developments occurs in a short period.

Then, after that exponential growth, the rate of change tapers right back off as another wall is hit. And basically, rinse and repeat until the next leg up.

I’ve noticed that my progress on a personal level follows a similar trajectory.

When I say something like “I worked on this project for over two years,” around half of that time really consisted of slow days, where I didn’t get much done. It could be as little as a sentence written.

Maybe another quarter of that time is spent completely away from the project. Where I did not even attempt to do any work on it. Whether due to a lack of ideas, feeling unwell, or something else.

Not even thinking or touching it.

It’s that last quarter where a majority of progress was made. Out of those two years, to use that example, I would say 70% of the project was developed during those few months.

These values are super arbitrary, but in general, most of my work done on any long-term endeavor could be summed up in 2–3 burst cycles, with glacially slow progress in the rest of the time spent.

Because of this, I’m inclined to believe that some things simply take time. Obviously, time alone doesn’t change anything, but I’d say the circumstances that evolve during its passage certainly do.

All it took was that little nugget of information to reveal itself.

Downtime

There was a bug in a program that I could not figure out for days. I was convinced that my logic was correct. But it turns out it wasn’t. It took days to break that bias and find that different perspective.

Yet the fix itself took only minutes. Most of the work was trying to re-approach with a fresh mind.

This is where other pursuits could’ve been utilized.

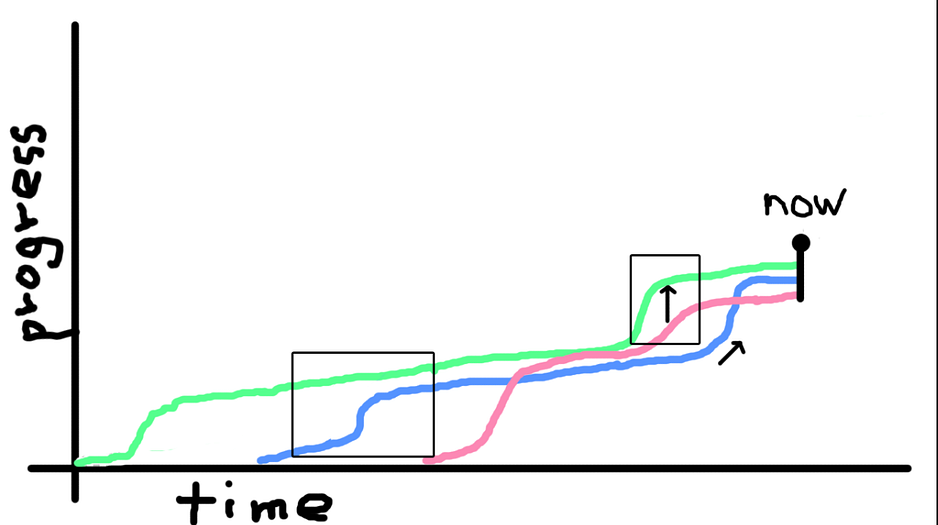

In the leftmost box in the figure, the slow period of the green endeavor is utilized to focus more heavily on a new blue endeavor. And so lots of progress is still made during that time, albeit in a different area.

For example, let’s say green is game development, and blue is 3D printing. At first, starting a new game project was slow. I had no idea how to start the story, what features I wanted, or any real direction.

After a while, I managed to find that direction and got ramped up. But after getting all the main features done and writing the draft, I got stuck on how to polish and integrate that story.

I quickly progressed and did most of what I was capable of doing at the time, but hit a wall and lost that fervor just as fast.

A couple of words a day was all I could muster, if even that. I was borderline hating this project now. I’d get much more done working at 80% in 15 minutes than at 2% in 15 hours.

So as I tried to unlock the next wave of new ideas and motivation— that new burst of progress, I started something new and exciting that I would enjoy much more.

3D printing, for example. I couldn’t understand the mechanics behind it at first. And so my failed prints were high.

But eventually, I learned what layer height is optimal, what temperatures were working, and what all the settings meant.

So while I was essentially rate-limited in game development, I could better use my time in pursuits where the momentum was already at a high. I would still be working on everything, of course.

But focus would be put where progress was already occurring.

Once a breakthrough was reached in one of the previous activities, I could return that focus to wherever it had occurred.

The work done or knowledge gained during a productive burst wasn’t undone because no work was done after. Fifty writings spread over a year versus fifty done in a month, are both still 50 writings the next year.

As time progressed and the past grew, the work ultimately became the same. They bore similar fruits of labor, before their utility tapered off as well.

This is why I’m not too concerned with finishing projects as early as possible anymore. Particularly, when that earliness might not actually be attainable.

There may be a slight advantage with having them out for longer, but ultimately, the impact of a few months difference, or even years, will probably be minimal. It’ll likely run its course before tapering off as well.

On the contrary, there’s no telling when the knowledge and experience in other areas will be utilized once again. They may even re-emerge in a completely unexpected place.

My stagnation may be more indicative of having already done most of what I’m capable of at the moment. I’d need time to ascertain the conditions to unlock the next level and progress to it. Perhaps, I may even stumble upon it by accident.

Pull Up

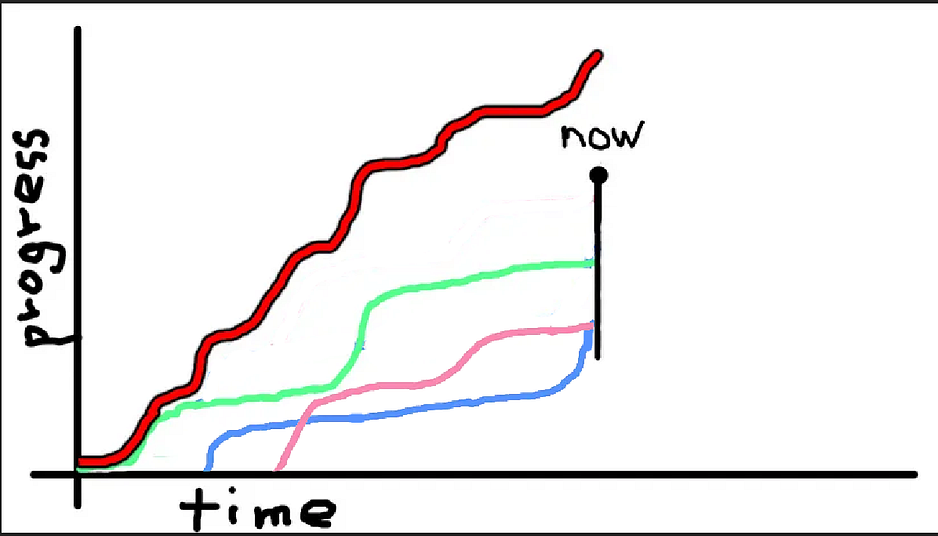

In the rightmost box of the illustration, the pink endeavor reveals new ideas that can be applied to the green endeavor, and so as a result, the pink pushes up the progress of the green.

Using game development as an example again — I’ve been working on improving my pacing and making all the elements cohere better with each other.

However, game dev isn’t the only area where this is beneficial. Pacing, visuals, and audio also are useful in things such as video production. And so by getting better at one, I got better at the other.

Now in the interest of fairness, both can have cinematic aspects, and so they are quite similar in that regard.

But even vastly different pursuits have had overlap.

Learning to fish can spark an article idea to write. Or serve as inspiration for a fishing-related game. Perhaps, the laid-back vibe of a fishing trip can improve my mental state, and allow me to think better for the time being.

Perhaps that fishing becomes so fun that game development falls into the background. Many months may go by without me even thinking of working on my project.

When I do decide to pick up work again, it feels new once more. I can take advantage of the excitement and motivation which that feeling brings. And I can apply any new ideas obtained since then in a much shorter time.

I’ll still have the experience and knowledge from the prior bursts as well.

Lining Up The Curves

By lining up endeavors so that the bursts of progress covered the others' slow times, I believe this led to more efficient and enjoyable time spent learning and making progress overall.

However, it was difficult to see this.

My focus was only on one line at a time.

It’s possible that none of these lines will reach the level of expertise I’d have reached by focusing solely on one. But observing these stagnant periods, I think each pursuit is progressing nearly as fast as I’m capable of.

But even if I’m not perfectly optimal, I’m not particularly concerned.

I think good enough should be good enough.

I’ll probably never make a soundtrack that’s mixed as well as an audio engineer in a studio. But after years of random knob and button pressing, I think I can make something decent enough to work.

Neither will I create any art assets that look good enough to use in my games. Though the years spent trying out different image manipulation software can be utilized for other purposes.

Again though, this is a bit misleading. Because I didn’t spend years on these endeavors in a continuous sense. Rather, it was a bunch of multi-month bursts within those years.

It was intertwined, spread amongst those prolonged periods of frustration and giving up. Amidst starting tons of other new things to distract from that.

Only to hit the same walls there.

After years of swapping between pursuits, I’ve learned a whole lot. I’ve been exposed to a lot of different things. But my short attention span won’t be satiated any time soon.

So I guess I’ll keep feeding it.

Therefore, as I continue this slow trudge to write articles, progress my game, and find code bugs, I’ll try and keep that feeling of newness alive in other areas. I’ll squeeze out progress and chain those exponents.

There’s no telling when a long-dormant path will come up again. As a matter of fact, I’m about to embark on something I haven’t done since third grade—fifteen years ago as of the time of writing.

So as the lines continue to push and pull on each other, they’ll hopefully keep rising together. Some may falter, and some may disappear. But the cumulative will continue on.

Eventually, I’ll get to a pretty good point in them all.

And I’ll only keep progressing from there.